by Michael Christie, The Ruggist

The impetus behind the making of a handknotted carpet from ECONYL® regenerated nylon.

To have a frank discussion about the role of plastics – including nylon – in our daily lives is to wade into precarious territory full of contradiction and often devoid of good faith dialog. On one extreme are ardent environmentalists who espouse a complete overhaul of civilization en masse and on the other are those who see the problem – if it exists at all – as something that the future will have to deal with. At the same time the former group is now protesting to raise awareness of climate change, so too are there those amongst them enjoying triple mocha lattes from disposable, single use plastic cups from Starbucks; the ease and convenience of the ‘Throwaway Living’ lifestyle both as featured in a 1955 issue of Life Magazine1 – and as promoted by the latter group – being a hard addiction to break. As a realist it must be said that plastic is here to stay – quite literally given its general lack of biodegradability – and society must come to terms with how to minimize its use as well as how to effectively utilize and reüse existing plastics; change is indeed required and the future is now.

A prototypical American nuclear family is – thanks in part to disposable plastics – shown embracing ‘Throwaway Living’ as featured in a 1955 Life Magazine feature promoting the concept.

Styled photograph by Peter Stackpole appearing under the Fair Use Doctrine.

The responsibility to implement these changes to the ways plastics are used lies not in some think tank, government, non-governmental organization, or the like; though certainly we depend upon them for the ‘grand plan.’ Rather it is a personal responsibility each of us must bear either as average citizens and consumers, through our consumption decisions, or as makers, influencers, and innovators who rethink the way each of our own industries utilize plastics – and the myriad resources of this planet. As such, this project, the making of a handknotted carpet from ECONYL® regenerated nylon explores the responsibility of each of its principals and our individual reasons for participating.

‘Since helping the Allies win World War II—think of nylon parachutes or lightweight airplane parts—plastics have transformed all our lives as few other inventions have, mostly for the better. They’ve eased travel into space and revolutionized medicine. They lighten every car and jumbo jet today, saving fuel—and pollution. In the form of clingy, light-as-air wraps, they extend the life of fresh food. In airbags, incubators, helmets, or simply by delivering clean drinking water to poor people in those now demonized disposable bottles, plastics save lives daily.’

Laura Parker(1)

The prototype handknotted carpet made from ECONYL® is shown from the weaver’s perspective looking down at balls of ECONYL® yarn soon to become part of the finished piece. | Photograph by Prabal Ratna Tuladhar.

‘As a new rug designer I was excited by the challenge that this project brings — ocean inspired pieces that don’t damage the earth,’ says British designer Isobel Morris about her involvement in this project. ‘I have a passion for eco-friendly solutions for wildlife and the environment, I’m dedicated to a better quality of life for myself, society, and future generations. Econyl offers a versatile solution for the rug and carpet industry [amongst many] and I’m proud to create designs with what I believe is the future of textiles.’

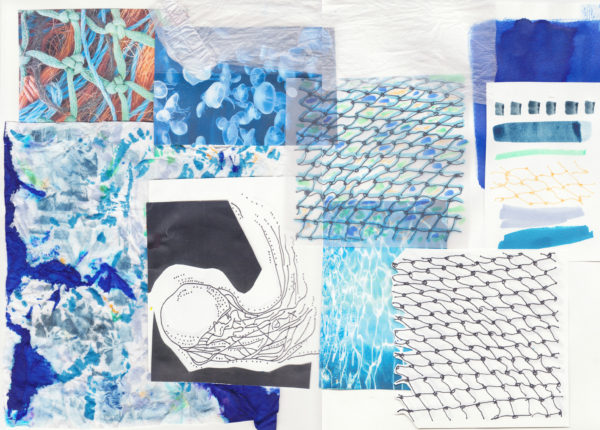

A moodboard of ideas which lead to the design concept for the prototype handknotted carpet made of ECONYL® brand nylon. Original artwork and concept by Isobel Morris for Sarawagi Rugs. | Scanned image courtesy of Isobel Morris.

Morris’ comments are reflective of a generational zeitgeist rooted in optimism, yet constrained by the very real problems facing human civilization. They hint at rejecting conservative-minded talking points that environmentalism will kill the economy, favouring instead to rethink, to reïmagine, to regenerate if I am to borrow phrasing from ECONYL®, the economy into one that not only provides for human needs, wants, and desires but protects the planet in the process. Morris again, ‘Social responsibility is important to me and many others. This partnership offers the amazing opportunity to reduce textile waste and collaborate with influential brands; Econyl and Sarawagi Rugs and industry expert The Ruggist.’

‘Ocean plastic is not as complicated as climate change. There are no ocean trash deniers, at least so far. To do something about it, we don’t have to remake our planet’s entire energy system. ‘This isn’t a problem where we don’t know what the solution is,’ says Ted Siegler, a Vermont resource economist who has spent more than 25 years working with developing nations on garbage. ‘We know how to pick up garbage. Anyone can do it. We know how to dispose of it. We know how to recycle.’ It’s a matter of building the necessary institutions and systems, he says—ideally before the ocean turns, irretrievably and for centuries to come, into a thin soup of plastic.

Laura Parker(1)

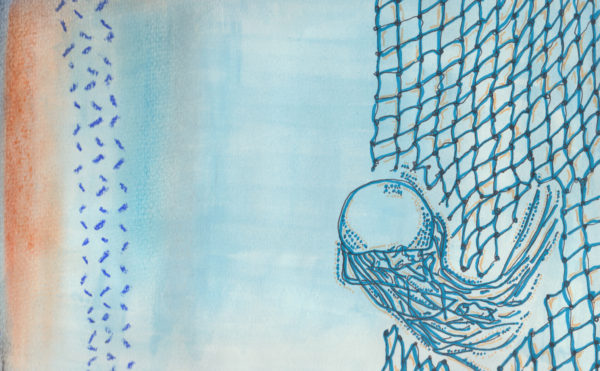

‘This collection emphasizes the detrimental impact of waste plastics on our oceans with a focus on the environmental sustainability of reüsing textiles with an industry first collection created from 100% recycled nylon – sourced from reclaimed nylon waste including derelict fishing nets,’ states Morris. Her vision for the carpet is one that highlights familiar if not also iconic imagery from the ocean, namely ocean ripples mirrored on the sea bed, with more topical forms evocative of humanity’s impact, in this case tangled fishing nets, layered into the final design. Complemented with a bold coastal and marine palette consisting of ‘chilled turquoise blues, cool white tones, and dramatic deep navy with a zap of orange’ the prototype carpet embodies the inviting spirit of the sea and the challenges of cleaning our polluted oceans.

To live in the early twenty-first century is to experience a period of irascibility I, nor perhaps many others as a teenager or young adult at the fine de siècle never foresaw; calling someone ‘crazy’ seems almost quaint given the political and social realities of this time. It is, however, a sentiment I share with Bonazzi. I myself having been called ‘crazy’ – amongst other things – at various points in my career. After all, who would choose a career writing about the handmade rug and carpet industry? Fortunately like Bonazzi, I too did not know.

And is that not the greatest of human abilities? To not know and then to endeavour to find out, to learn.

The initial drawing of the as of October 2019 unnamed prototype handknotted carpet made of ECONYL® brand nylon. Original artwork and concept by Isobel Morris for Sarawagi Rugs. | Scanned image courtesy of Isobel Morris.

The truth be told I get approached by a lot of rug makers to be involved in projects of various merit. Often times they think I can help them sell rugs, other times they think I can write miraculous copy that will make even the most mediocre of carpets sounds amazing. (Note: I was never an amazing salesman and I only write about carpets I find interesting.) Few of these offers resonate with me the way this project with ECONYL® did.

By combining with the craft of handknotted carpet making, a sustainably produced fibre that also helps clean up the planet, this project dares to ask the questions we must ask if we are to solve the environmental problems facing our planet. Most notably, ‘How can each of us help within our own industries?’ and ‘What new and newfound ways can we do things in order to accomplish this goal of righting the planet?’ This is the attraction and the reason I became involved. I feel civilization has faced no greater obstacle to our continued existence and we must each do our part, for without an environment, ‘What have we?’ I ask rhetorically. Even if my part is only as conceptualist and documentarian, if it inspires others to question their methods, and if necessary make changes, I feel this project will be considered a success; for me, for ECONYL®, for Sarawagi, for Isobel Morris, for the planet Earth.

Balls of dyed ECONYL® brand nylon yarn await knotting into the prototype handknotted carpet made from the material. Note the sheen differences employed to mimic the inherent lustre differences between wool and silk. | Photograph by Prabal Ratna Tuladhar.

And what of Sarawagi Rugs of Kathmandu, Nepal? How is it that they fit into this realization of a handknotted carpet made from ECONYL®? In actuality it is Shally Sarawagi who instigated the project by first exploring how ECONYL® fibres would work in a handknotted carpet. From the moment she showed me the first diminutive sample at Sarawagi’s offices in Kathmandu, to the time we were enjoying lunch and she inquired as to whether or not the beverage she ordered came with a plastic straw, her environmental mindset is perhaps the most top of mind and prescient.

Nepal is a poor country, ranking 161 out of 191 countries when ranked by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per person, adjusted for relative purchasing power2

. It is also a very polluted3 and litter covered country. Owing partially to relative wealth and to basic human traits, namely laziness, that even in this writer’s lifetime were once common in the United States, to walk around Kathmandu, the Nepali countryside, and even Mount Everest4 is to experience pollution at it’s most visible: litter. This is the environment alluded to in 19875 that would come to pass in a little more than thirty years time as the Kathmandu Valley transformed from a collection of bucolic villages into a sprawling, if not also contained, metropolis. It is also the same one Shally Sarawagi grew up in and the same one which informs her very spirit. ‘How can we not try to do better? We have to,’ she once emphatically stated to me in discussion of improving the environment.

The Kathmandu Valley of Nepal as it appeared in the July 1987 National Geographic article ‘At the Crossroads of Kathmandu.’ | Photograph by William Thompson appearing under the Fair Use Doctrine.

Agricultural land once filled the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal, but now – due to development – only pockets remain. These rice paddies were being planted when this July 2019 photograph was taken. | Photograph by The Ruggist.

A cityscape view of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal captured from the rooftop of Alternative Technologies, makers of Galaincha software, as it appeared in July 2019. | Photograph by The Ruggist.

This project, the creation of a handknotted carpet made from ECONYL® regenerated nylon exists within the microcosm of the handknotted rug and carpet industry; its relative impact on the global economy and environment pale in comparison to much larger and more polluting industries. This is however not to say improvements cannot be made and novel innovations cannot contribute more broadly to solving the problems facing the world. Moreover, it represents the kind of collaborative and unexpected efforts required to affect such change.

From the involvement of an Italian multinational with thousands of employees in six (6) countries on three (3) continents supplying the regenerated yarn, to a second-generation Nepali rug and carpet manufactory adapting to changing market conditions, to a young British designer with eyes focused clearly on the future of textiles, to a dual Canadian/American commentator and writer of rugs and carpets with a penchant for the interesting, the principals of this project form a multicultural coälition. While improving the environment is certainly the main – and if we are being frank, marketable – goal, this is done within the context of providing for human wants, needs, and desires; a partnership – a coälition if you will – which balances disparate perspectives, cultures, needs, and so forth, to craft a solution workable for the planet and us all.

The prototype handknotted ECONYL® carpet will debut at Domotex in Hannover, Germany, 10-13 January 2020. See the carpet for yourself and listen to a panel discussion lead by this writer as we discuss all there is to know about this project, the carpet, and how we can each to our part.

This article is part three of a five part series; part two can be found here.

1. Parker L. We Made Plastic. We Depend on it. Now We’re Drowning in it. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/06/plastic-planet-waste-pollution-trash-crisis/. Published June 2018. Accessed October 2019. 2. Ventura L. The World’s Richest and Poorest Countries 2019. Global Finance. https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/economic-data/worlds-richest-and-poorest-countries. Published April 22, 2019. Accessed October 2019. 3. Groves S. Nepal’s Air Pollution Threatens Humans and Glaciers. PRI – Public Radio International. https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-04-06/nepal-s-air-pollution-threatens-humans-and-glaciers. Published April 6, 2017. Accessed October 2019. 4. Sharma B, Schultz K. How Do You Get 200,000 Pounds of Trash Off Everest? Recruit Yaks. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/20/world/asia/mount-everest-trash-nepal.html. Published March 20, 2018. Accessed October 2019. 5. Chadwick DH. At the Crossroads of Kathmandu. National Geographic. 1987;171(6):32-65.